06. Do you know where flour comes from?

Dipping our toes into the world of wheat.

Hello!

Welcome to the Roll with it Newsletter. I’m happy you found me!

I’m switching it up and posting mid week! Hopefully this will give you a chance to digest all this information before the linked recipe is released on Sunday.

Today we’re going to be chatting all about flour. We use flour to make bread, batters, cookies, crumbles, pasta, pancakes (the list could go on and on) but do you really know where your flour comes from and why we use it?

Well, let’s find out…

But first, some housekeeping. There is now a ‘Pledge’ subscription button. This is an opportunity for you to pledge a payment in support of my writing and recipe development. You won’t be charged until I decide to turn on paid subscriptions. When I do, paid subscribers will have access to bonus content, the recipe archive, community threads and more! If ya wanna show me some love, I’d be very grateful but obvs no pressshh!

Cissy… xo

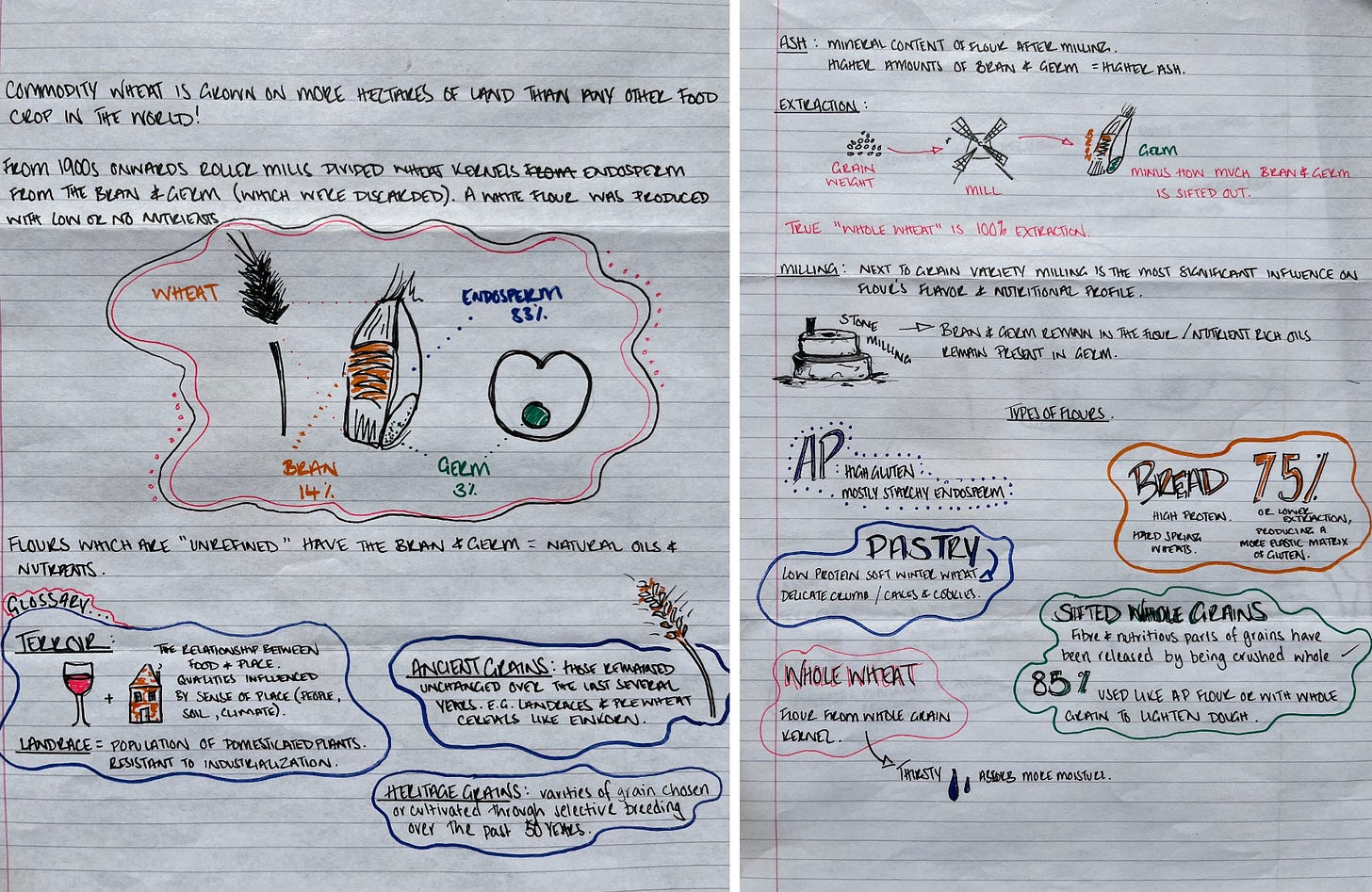

Despite having worked with flour my whole life, from rustling cupcakes up as a kid to lugging kilos of the stuff around a bakery, it wasn’t until COVID-19 that I delved deeper into what it really means to work with this ingredient. During this time (like most of us) I was on the lockdown sourdough buzz, banging out loaves everyday. However, I was also listening to an amazing series on Farmerama Radio called ‘Cereal’. Every day for a week I would sit in my sister’s spare room listening to this 6 part series, taking notes and scribbling down drawings to help me consume all the information. Through the interviews on the show with farmers, millers and bakers I was introduced to a new way of understanding flour. In a weird but on occasion wonderful time, I’m so thankful I found this programme as it became a meditation for me and has informed my work in the subsequent years. I urge you to go and listen to it! For now, we will run through some of the key topics.

Flour is a natural product made by milling grains. The most common grain used to make flour is wheat. It’s likely you would have passed by golden wheat fields in the countryside or if lucky enough, walked through the tram lines of a wheat field, brushing your hands against the top of the plant, feeling its bristly beard and hearing the whooshing of the wind through the uniform rows. Yes, this sounds nostalgic and for good reason! I grew up on the edges of a working farm, where wheat and rapeseed were harvested. To my knowledge, the grain was only used for cattle feed but I like to think that it informed my life as a baker, as I will always remember running out into the fields, dipping down low, hiding from my sister between the reeds, and riding with the farmers on (what seemed at the time) gigantic combine harvesters, cutting the wheat until the my dinner time.

Where does flour come from?

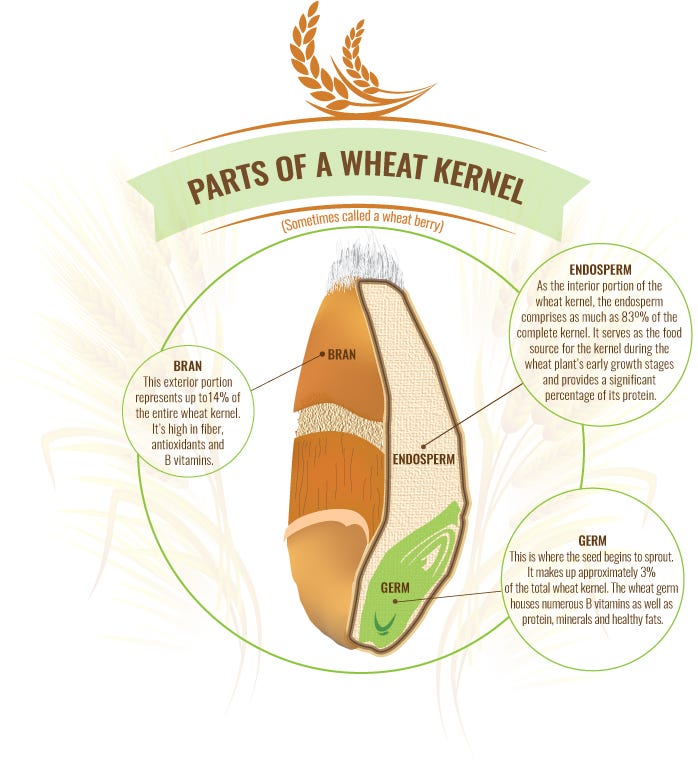

The ‘Fertile Crescent’ in the West of Asia is where cereals such as wheat and barley were first domesticated (grown for human consumption). Since then (around 10,000 years ago) we have industrialised the production of wheat through two technological revolutions, both of which had huge effects on us and the wheat itself. Firstly, in the 19th century, the invention of the steel roller mill revolutionised the way grain was milled. Compared with stone mills, steel was more efficient and allowed for more control over which parts of the kernel were milled (more on this in a bit but the kernel is divided into 3 sections, the endosperm, the bran and the germ. Each have different nutritional qualities). Producers wanted to discard all the bran and germ, keeping only the endosperm, which is the white part of the wheat kernel (high in protein and carbs). This meant a very pure white flour could be stored for a very long time and produced at a very low cost. It also meant that most stone mills started to disappear, which meant a sharp decline in localised food economies (at the time most towns had their own mill).

Alongside this, the ‘Chorleywood bread process’ was invented after the War. This was when the UK could no longer import high protein flours (= good for bread) so had to use wheat grown on the land which was much softer and lower in protein (= not so great for traditional methods of making bread). In order to mimic what the harder, stronger flours could achieve the Chorleywood process added preservatives, yeast, enzymes and oxidants to its loaves, which created an ultra fluffy, soft bread that could be made in half the amount of time and for half the cost. Although this loaf remains the most popular, it is actually so nutritionally void that producers had to add back in synthetic vitamins and irons, which are naturally found in the wheat kernel’s bran and germ. (I mean…that makes zero sense?!)

Note: in some countries (including the US but not the UK/EU) commercial mills bleach their flour. This speeds up the ageing process, which is when the flour oxidises, changing from yellow to white, and the gluten is strengthened. Not only this, some flours (like white sliced bread) is fortified. A practice that came about during rationing to help enhance the nutritional benefits of flour. Look out for this on the back of supermarket flours. You can read a debate about whether this is good or bad here.

At the same time, (seemingly) ‘new and improved’ methods of farming were introduced, which involved the use of synthetic fertilisers, pesticides and propagating new strains of wheat to increase yields. This modern variety of wheat is quite unlike its ancient relatives because it is so uniform and lacking in genetic diversity.

In recent years, there has been a movement to start growing better grain here in Ireland and in the UK, in a way that is good for the soil, our climate, our farmers, our bread and our bodies. However, it is very hard to change people’s mindset that flour and bread should be cheap products with a long shelf. In the same way you might consider buying better meat, flour should be thought of in the same way. Knowing where it comes from, not the shop, but which country, on what soil and how it was treated will help you as a baker make informed decisions about how to use it. Ultimately, you’ll end up with a better flavour, crumb, crust and rise. Just remember to ask yourself these questions - is this flour fresh? Do I know where this flour comes from? Does this flour have other ingredients in its ingredients list?

Common types of flour

Plain flour: this is the most commonly found flour. It is mostly made up of the starchy endosperm.

Strong white flour: this is high in protein which is great for building a ‘strong’ dough.

Pastry flour: is typically a soft wheat which makes it ideal for cakes that need a delicate crumb.

Wholegrain: this is made from the whole grain kernel. Supermarket ‘whole grain’ flours are usually just plain flours with some of the bran added back in.

Self raising: this is a plain white flour mixed with the leavening agent baking powder.

Heritage: varieties that have existed for more than 50 years, may include hybrids but were generally abandoned when modern wheat, uniformity, and higher yields were introduced.

Ancient: grains that have remained unchanged for the last several hundred years. Includes ‘pre-wheat’ cereals such as einkorn, emmer and spelt.

Emmer: a wild wheat that is a hybrid of goat grass and wheat. Originating in Italy.

Einkorn: a grain more easily digestible than modern wheat when it has been slowly fermented. It’s high in vitamins and minerals and tastes nutty and grassy. Low in gluten.

Spelt: an ancient grain that is more easily digestible than modern wheat because of its low levels of gluten and higher soluble fibres. It has remained unchanged since biblical times.

Milling

Stoneground: this is when the grain is crushed between stones. This flour has some of the bran and germ left in it. The bran and the germ are both nutritionally better for you and full of more flavour.

Roller: this is when the grain is crushed at a high heat between steel rollers. The bran and germ are sifted out and then the flour is milled again. Generally commercial flour is all milled to the same specification.

Gluten

The holy grail. The mothership. What we live for!

Gluten is a protein that helps build ‘strength’ and elasticity in a dough. When flour is hydrated it immediately starts forming these gluten bonds. During mixing these bonds multiple. When making bread, for example, these chains elongate and get stronger. This results in a complicated gluten matrix, which makes the dough extensible and elastic. The net also captures CO2 released during fermentation, which is what gives some breads that super open, airy crumb structure.

All flours have different gluten-forming abilities and need different amounts of hydration to suit. They also have different flavour profiles and textures. Flour should be treated like any other raw ingredient.

Some suppliers to look out for are…

Oak Forest Mills

The Little Mill

Irish Organic Mill

Dunany

Shipton Mill

Doves Farm

Wildfarmed

This is a very small snippet into the world of flour. We’ll be revisiting it time and time again.

If you want to know more, here are some resources (this is not a prescriptive list) - people doing interesting things to help change our current systems, podcasts and more. Please also feel free to ask me any questions! I’m here at your disposal. Or if you know of anyone who similarly loves flour, grows it, mills it, bakes with it, I wanna know and hear from them too!